Papska država

| Papska država Stato della Chiesa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

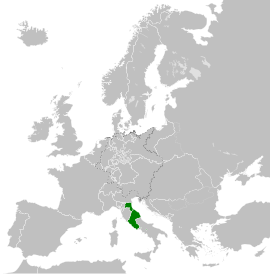

Papska država 1815. posle Napoleonovih ratova | |||

| Geografija | |||

| Kontinent | Evropa | ||

| Regija | Apenini | ||

| Prestonica | Rim | ||

| Društvo | |||

| Službeni jezik | latinski, italijanski, oksitanski | ||

| Religija | Rimokatolička | ||

| Politika | |||

| Oblik države | Teokratska apsolutistička monarhija | ||

| — Papa | Papa Stefan II (prvi) | ||

| Papa Pije IX (poslednji) | |||

| Istorija | |||

| Postojanje | |||

| — Osnivanje | 754. | ||

| — Ukidanje | 1870. | ||

| Događaji | |||

| — Osnivanje | 754. | ||

| — Nezavisnost od Svetog rimskog carstava | 1177. | ||

| — Kraj Papske države | 20. septembar 1870. | ||

Papska država ili Papske zemlje (ital. Stato della Chiesa) je ime istorijske italijanske države koja je postojala od 754. do 1870.[1] Službeni naziv bio je Patrimonium Sancti Petri. Grad Vatikan je minijaturna država naslednik Papske države.

Istorija

[uredi | uredi izvor]Rana istorija

[uredi | uredi izvor]Pipin Mali je sredinom 8. veka osvojio veći deo severne Italije i poklonio prostor bivšeg Ravenskog egzarhata rimokatoličkom papi Stefanu II. Ovaj istorijski akt je poznat kao Pipinov poklon. Karlo Veliki je 781. kodifikovao i odredio teritorije na kojima Papa ima suverenitet. Teritorija je obuhvatala Rim i okolinu, ali i Ravenu, Pentapolis i Vojvodstvo Benevento, Toskanu, Korziku, Lombardiju i još neke gradove. Saradnja papstva i Karolinške dinastije je kulminirala 800. kada je Papa Lav III krunisao Karla Velikog za prvog germanskog „Cara Rimljana“ (Augustus Romanorum). Međutim, u prva tri veka postojanja Papske države, Papa nije imao efektivnu kontrolu nad celom državom, niti je bilo jasno da li je Papska država nezavisna u odnosu na Sveto rimsko carstvo.

U 10. veku, car Oton I je sklopio ugovor sa Papom po kojem je Papskoj državi potvrđen suverenitet i nezavisnost. Ovo pitanje je i dalje ostalo predmet sukoba papstva i carstva, sve do oko 1300. kada je nezavisnost Pape prevagnula.

Od 1305. do 1378, Pape su stanovale u Avinjonu, u južnoj Francuskoj. Papska država je tada samo formalno bila pod njihovom kontrolom. Grad Avinjon je bio deo Papske države, i ostao njen posed sve do Francuske revolucije.

Papska država na vrhuncu moći

[uredi | uredi izvor]Tokom Renesanse, teritorija Papske države se proširila, najviše pod Papama Aleksandrom VI i Julijem II. Pape su postale jedne od najvažnijih italijanskih svetovnih vladara, pored svoje uloge u Crkvi. U praksi, većinom papskih poseda su vladali mesni prinčevi. Tek u 16. veku su Pape uspostavile potpunu kontrolu nad svojim teritorijama.

Na vrhuncu teritorijalne ekspanzije, u 18. veku, Papska država je obuhvatala većinu centralne Italije: Lacij, Umbriju, Marku, Ravenu, Feraru, Bolonju i delove Romanje. Takođe je uključivala enklave u južnoj Italiji i okolinu Avinjona u Francuskoj.

Doba revolucija

[uredi | uredi izvor]U periodima 1796—1800. i 1808—1814, francuska revolucionarna armija je pretvorila Papske posede u Rimsku republiku, a kasnije u deo Francuske.

Italijanski nacionalni revolucionari su 1849. proglasili Rimsku republiku, dok je Papa Pije IX pobegao iz Rima. Francuske trupe Luj Napoleona Bonaparte i Austrije su porazile revolucionare i vratile Papu na vlast.

Ujedinjenje Italije — kraj Papske države

[uredi | uredi izvor]Godine 1860, država ujedinitelj Italije — Sardinija, pripojila je Bolonju, Feraru, Umbriju, Marku i Benevento Italiji. Ove teritorije su bile približno dve trećine Papske države. Pod papskom kontrolom je ostao region Lacij u okolini Rima. Tako je pokrenuto Rimsko pitanje, t. j. pitanje suvereniteta nad gradom Rimom.

Papski suverenitet u Rimu je štitio francuski garnizon. Ovaj garnizon se povukao jula 1870. zbog izbijanja Francusko-pruskog rata. U septembru, Italija je objavila rat Papskoj državi i osvojila Rim 20. septembra. Papa Pije IX se povukao iz svoje uobičajene rezidencije Palate Kvirinale u Vatikan i proglasio se zarobljenikom.

Kasnije, 1929, Papa Pije XI formalno se odrekao poseda Papske države i potpisao Lateranski sporazum sa Italijom, kojim je formirana država Grad Vatikan. Ova država je suverena teritorija Svete Stolice, koja je sama po sebi subjekt međunarodnog prava.

Reference

[uredi | uredi izvor]- ^ „Papal States”. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 30. 4. 2020.

Literatura

[uredi | uredi izvor] Ovaj članak uključuje tekst iz publikacije koja je sada u javnom vlasništvu: Herberman, Čarls, ur. (1913). „States of the Church”. Katolička enciklopedija. Njujork: Robert Eplton.

Ovaj članak uključuje tekst iz publikacije koja je sada u javnom vlasništvu: Herberman, Čarls, ur. (1913). „States of the Church”. Katolička enciklopedija. Njujork: Robert Eplton.- Chambers, D. S. (29. 9. 2006). Popes, Cardinals and War: The Military Church in Renaissance and Early Modern Europe. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 1-84511-178-8.. [sic]

- De Cesare, Raffaele (1909). The Last Days of Papal Rome. London: Archibald Constable & Co.

- De Grand, Alexander J. (2004). Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: The "fascist" Style of Rule. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415336314.

- Domenico, Roy Palmer (2002). The Regions of Italy: A Reference Guide to History and Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313307331.

- Elm, Kaspar; Mixson, James D. (2015). Religious Life between Jerusalem, the Desert, and the World: Selected Essays by Kaspar Elm. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004307780.

- Fischer, Conan (2011). Europe between Democracy and Dictatorship: 1900 - 1945. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1444351453.

- Gross, Hanns (2004). Rome in the Age of Enlightenment: The Post-Tridentine Syndrome and the Ancien Régime. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521893787.

- Hanlon, Gregory (2008). The Twilight Of A Military Tradition: Italian Aristocrats And European Conflicts, 1560-1800. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135361433.

- Hanson, Paul R. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution

(2nd izd.). Rowman & Littlefield. str. 252. ISBN 978-0810878921. „Comtat Venaissin and Avignon were annexed by France.”

(2nd izd.). Rowman & Littlefield. str. 252. ISBN 978-0810878921. „Comtat Venaissin and Avignon were annexed by France.” - Kleinhenz, Christopher (2004). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135948801.

- Levillain, Philippe (2002). The Papacy: Gaius-Proxies. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415922302.

- Luther, Martin (1521). Passional Christi und Antichristi. Reprinted in W.H.T. Dau. At the Tribunal of Caesar: Leaves from the Story of Luther's Life. 1921.. St. Louis: Concordia. (Google Books)

- Menache, Sophia (2003). Clement V. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. str. 142. ISBN 978-0521521987.

- Roessler, Shirley Elson; Miklos, Reny (2003). Europe 1715-1919: From Enlightenment to World War. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742568792.

- Ruggiero, Guido (2014). The Renaissance in Italy: A Social and Cultural History of the Rinascimento. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1316123270.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2013). Western Civilization: A Brief History (8th izd.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1133606765.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804726306.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851096725.

- Waley, Daniel Philip (1966). Rearder, Harry, ur. „A Short History of Italy: From Classical Times to Present Day”

. University Press. „1332 John XXII vicars.”

. University Press. „1332 John XXII vicars.” - Watanabe, Morimichi (2013). Izbicki, Thomas M.; Christianson, Gerald, ur. Nicholas of Cusa – A Companion to his Life and his Times. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1409482-536.

- Adiele, Pius Onyemechi (2017). The Popes, the Catholic Church and the Transatlantic Enslavement of Black Africans 1418-1839. Georg Olms Verlag..

- Aradi, Zsolt. (1955). The Popes The History Of How They Are Chosen Elected And Crowned. Farrar, Straus And Cudahy.

Bauer, Stefan (19. 12. 2019). The Invention of Papal History: Onofrio Panvinio between Renaissance and Catholic Reform. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198807001.

- Buttler, Scott; Dahlgren, Norman; Hess, David (1997). Jesus, Peter & the Keys: A Scriptural Handbook on the Papacy. Santa Barbara: Queenship. ISBN 978-1-882972-54-8.

- Chadwick, Owen (1981). The Popes and European revolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826919-9.. covers 1789 to 1815

- Chadwick, Owen (1998). A history of the popes, 1830-1914. Oxford University Press., scholarly. A history of the popes, 1830-1914. 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-826922-9.

- Collins, Roger (2009). Keepers of the Keys: A History of the Papacy

. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01195-7.

. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01195-7. - Coppa, Frank J (2014). The Papacy in the Modern World: A Political History. online review

- Coppa, Frank J. ed. The great popes through history: an encyclopedia (2 vol, 2002) The great popes through history : An encyclopedia. 2002.

- Duffy, Eamon (2006). Saints & Sinners (3 izd.). New Haven Ct: Yale Nota Bene/Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11597-0.

- Fletcher, Stella (2017). The Popes and Britain: a history of rule, rupture and reconciliation. Bloomsbury Publishing..

- Lascelles, Christopher (2017). Pontifex Maximus: A Short History of the Popes. Crux Publishing Ltd..

- Mcbrien, Richard (1997). Lives of the Popes: The Pontiffs from St. Peter to John Paul II. San Francisco: Harper SanFrancisco. ISBN 978-0-06-065304-0.

- McCabe, Joseph (1939). A History of the Popes. London.: Watts & Co.

- Maxwell-Stuart, P. (1997). Chronicle of the Popes: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Papacy over 2000 Years. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01798-2.

- Norwich, John Julius (2011). Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy. Random House NY. ISBN 978-1-4000-6715-2., popular history

- O’Malley, S.J., John W. The Jesuits and the Popes: A Historical Sketch of Their Relationship (2016)

- Pennington, Arthur Robert (1882). Epochs of the Papacy: From Its Rise to the Death of Pope Pius IX. in 1878. G. Bell and Sons.

- Rendina, Claudio (2002). The Popes: Histories and Secrets. Washington: Seven Locks Press. ISBN 978-1-931643-13-9.

- Schatz, Klaus (1996). Papal Primacy from its Origins to the Present. Collegeville, MN..

- Schimmelpfennig, Bernhard (1992). The Papacy. New York.

- Toropov, Brandon (2002). The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Popes and the Papacy. Indianapolis: Alpha Books. ISBN 978-0-02-864290-1., popular history

- Vaughan, Herbert (2018). The Medici Popes. Jovian Press..

- Barraclough, Geoffrey (1979). The Medieval Papacy

. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95100-4.

. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95100-4. - Dunn, Geoffrey D., ed. The bishop of Rome in late antiquity (Routledge, 2016), scholarly essays.

- Housely, Norman (1986). The Avignon Papacy and the Crusades. Oxford University Press..

- Larson, Atria, and Keith Sisson, eds (2016). A Companion to the Medieval Papacy: Growth of an Ideology and Institution. Brill. online

- Moorhead, John (2015). The Popes and the Church of Rome in Late Antiquity. Routledge.

- Noble, Thomas F.X. “The Papacy in the Eighth and Ninth Centuries.” New Cambridge Medieval History, v. 2: c. 700-c.900, ed. Rosamund McKiterrick (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- Robinson, Ian Stuart (1990). The Papacy, 1073-1198: Continuity and Innovation. Cambridge..

- Richards, Jeffrey (1979). Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages, 476-752. London..

- Setton, Kenneth M. The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571 (4 vols. Philadelphia, 1976-1984)

- Sotinel, Claire. “Emperors and Popes in the Sixth Century.” in. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian, ed. Michael Maas. Cambridge University Press. 2005..

- Sullivan, Francis (2001). From Apostles to Bishops: The Development of the Episcopacy in the Early Church. New York: Newman Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-0534-2.

- Ullmann, Walter (1960). A short history of the papacy in the Middle Ages.