Semitski jezici

| semitski | |

|---|---|

| Geografska rasprostranjenost | jugozapadna Azija, severna Afrika, severoistočna Afrika, Malta |

| Jezička klasifikacija | afroazijski

|

| Prajezik | prasemitski |

| Podpodela | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | sem |

| Glotolog | semi1276[1] |

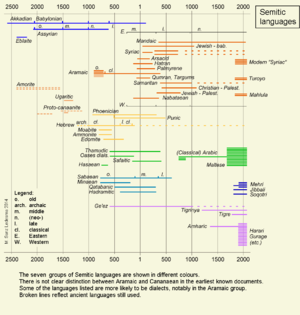

Približna istorijska distribucija semitskih jezika | |

Hronološko mapiranje semitskih jezika | |

Semitski jezici, ranije takođe poznati kao siro-arabijski jezici, grupa su srodnih jezika koji vode poreklo iz zapadne Azije.[2][3] Ove jezike govori preko 470 miliona ljudi u zapadnoj Aziji, severnoj Africi, Somaliji, Džibutiju, Eritreji i Etiopiji,[4] kao i u često velikim imigrantskim zajednicama u Severnoj Americi, Evropi i Australaziji.[5][6] Oni pripadaju afroazijskoj jezičkoj porodici. Najzastupljeniji semitski jezik jeste arapski, kojim govori oko 300 miliona ljudi,[7] potom amharski sa 22 miliona govornika,[8] zatim hebrejski kojim govori oko 7 miliona ljudi,[9] tigrinja jezik sa 6,5 miliona govornika[10], aramejski koji broji približno 575.000 do jednog miliona govornika,[11][12][13] i malteški (483.000 govornika).[14]

Semitski jezici se pojavljuju u pisanom obliku od vrlo ranog istorijskog datuma, a istočnosemitski akadski i eblajski tekstovi (pisani alfabetom prilagođenim iz sumerskog klinopisa) javljaju se od 30. veka p. n. e. i 25. veka p. n. e. u Mesopotamiji, u severnom Levantu. Jedini ranije atestirani jezici su sumerski, elamitski (2800. p. n. e. do 550 godine pne) (oba su jezički izolati), egipatski i nerazvrstani lulubi iz 30. veka p. n. e.

Poreklo

[uredi | uredi izvor]

Semitski jezici su se u pisanoj formi pojavili veoma rano, u 3. veku pre nove ere, u Mesopotamiji i severnom Levantu sa akadskim i eblaitskim tekstovima. Naziv semitski po prvi put su upotrebili nemački orijentalisti Avgust Ludvig fon Šlecer i Johan Gotfrid Ajnhorn, krajem 18. veka kako bi označili arapski, aramejski i hebrejski jezik.

Ludvig fon Šlecer je ovaj termin izveo iz imena Sem, jednog od tri Nojeva sina. Pre Šlecera, ovi jezici su u evropskoj literaturi bili poznati kao orijentalni jezici. U 19. veku, termin semitski postaje konvencionalan, ali su poneki pisci koristili naziv sirsko-arabljanski.

Semitski jezici su korenski jezici, što znači da se u korenu svake reči nalaze tri konsonanta, a ponekad i četiri, koji su i nosioci značenja, odnosno smisla reči. Pojmovi se ređe grade dodavanjem sufiksa i prefiksa, a češće ubacivanjem kratkih i dugih vokala između korenskih konsonanata. Na primer, u arapskom jeziku koren k-t-b nosi značenje „pisati“. Od ovog korena reči se grade dodavanjem vokala, na primer: kitāb „knjiga“, kutub „knjige“, kātib „pisac“, yaktubu „on piše“, kataba „on je pisao“, itd.

Reči u semitskim jezicima dele se na glagole, imena i čestice. Semitski jezici su veoma bliski, bliži nego indoevropski jedan drugom, s obzirom na to da u nekim grupama semitskih jezika postoje ukrštanja raznih osobina, zato njihovu podelu vršimo na osnovu njihovog geografskog položaja. Zato, unutar semitskih jezika pronalazimo tri velike grupe:

- Severoistočnosemitski jezici

- Severozapadnosemitski jezici

- Jugozapadnosemitski jezici

Severoističnosemitski jezici

[uredi | uredi izvor]Jedni od najstarijih pisanih tragova u istoriji čovečanstva sačuvani su upravo na akadskom jeziku kojim su tada govorili Asirci i Vavilonci, odnosno stanovnici drevne Mesopotamije. Oko drugog milenijuma pre nove ere, akadski jezik se razdvojio u dve grane, jezaka ili dijalekta: asirski i vavilonski.

Severozapadnosemitski jezici

[uredi | uredi izvor]

U ovu grupu spadaju jezici današnje Palestine i Sirije, a čine je:

- Kanaanski jezici

- Aramejski jezici

Kanaanski jezici nastali su krajem 2. milenijuma pre nove ere, a dele se na:

- Hebrejski jezik

- Fenički jezik, koji je bio u upotrebi od 10. do 1. veka pre nove ere

- Moabitski jezik, koji se upotrebljavao u 9. veku

Hebrejski jezik je jezik Jevreja, uobličio se iz starojevrejskih plemenskih dijalekata krajem 2. milenijuma pre nove ere. Klasičnim hebrejskim jezikom napisan je najveći deo Starog Zaveta, a Deborina pesma jeste najstariji spomenik na hebrejskom jeziku. U 19. veku nastao je novohebrejski jezik, i on postaje službeni jezik države Izrael nakon njenog formiranja 1948. godine.

Aramejske jezike delimo na tri grupe:

- Aramejski jezik

- Zapadnoarmejski jezik

- Istočnoarmejski jezik

Aramejski jezik grubo možemo podeliti na tri vremenske etape: staroaramejski (10–8. vek pre nove ere), klasični ili carski aramejski (7–5. veka p. n. e.) i biblijsko-aramejski (5–2. vek p. n. e.), na kojem je napisan i deo Starog Zaveta. Godine 500. nove ere, persijski imperator Darije proglašava aramejski jezik službenim jezikom zapadnog dela svog carstva. Od tada pa do 7. veka n. e., aramejski jezik će suvereno vladati Levantom i Mesopotamijom.

Zapadnoaramejski jezik delimo na:

- Nabatejski jezik (1. vek pre nove ere – 3. vek nove ere)

- Palmirski (1. vek p. n. e. – 3. vek n. e.)

- Judeopalestinski jezik (1. vek n. e.)

- Samarićanski jezik (4. vek n. e.)

- Hrišćanskopalestinski jezik (5–8. vek n. e.)

Istočnoaramejski jezik delimo na:

- Sirijački jezik (3–13. vek n. e.)

- Vavilonski aramejski jezik (5–6. vek n. e.)

- Mandejski jezik (3–8. vek n. e.)

Jugozapadnosemitski jezici

[uredi | uredi izvor]Područje nastanka jugozapadnih semitskih jezika je Arabljansko poluostrvo i oni se dele na:

Arapske jezike delimo na južne arapske jezike (sabejski, minejski, hadramautski i asuanski jezik) i severnoarapski jezik, odnosno arapski jezik. Etiopski jezici se dele na jezik geez, koji je bio u upotrebi oko prvog veka nove ere i moderne semitske jezike Etiopije, a to su jezik harari, jezik tigrinja i amharski jezik.

Živi semitski jezici i broj njihovih govornika

[uredi | uredi izvor]| jezik | govornici |

|---|---|

| Arapski | 206,000,000[15] |

| Amharski | 27.000.000 |

| Tigrinja | 6.700.000 |

| Hebrejski | 5.000.000[16] |

| Novoaramejski | 2.105.000 |

| Silte | 830.000 |

| Tigre | 800.000 |

| Sebat bet gurage | 440.000 |

| Malteški | 371.900[17] |

| Savremeni južno arabljanski | 360.000 |

| Inor | 280.000 |

| Sodo | 250.000 |

| Harari | 21.283 |

Reference

[uredi | uredi izvor]- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, ur. (2016). „Semitic”. Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ^ Bennett 1998. sfn greška: više ciljeva (2×): CITEREFBennett1998 (help)

- ^ Hetzron 1997.

- ^ Bennett, Patrick R. (1998). Comparative Semitic Linguistics: A Manual. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060217.

- ^ „2016 Census Quickstats”. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Arhivirano iz originala 30. 10. 2018. g. Pristupljeno 26. 8. 2018.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25. 10. 2007). „Sydney (Urban Centre/Locality)”. 2006 Census QuickStats. Pristupljeno 23. 11. 2011. Map

- ^ Jonathan, Owens (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Arabic Linguistics. Oxford University Press. str. 2. ISBN 978-0199344093. Pristupljeno 18. 2. 2014.

- ^ Amharic na sajtu Ethnologue (18. izd., 2015)

- ^ Modern Hebrew na sajtu Ethnologue (18. izd., 2015)

- ^ Tigrinya na sajtu Ethnologue (18. izd., 2015)

- ^ Assyrian Neo-Aramaic at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ^ Chaldean Neo-Aramaic at Ethnologue (14th ed., 2000).

- ^ ^ Turoyo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ^ Ethnologue Entry for Maltese, 21st ed., 2018

- ^ Ethnologue: "206,000,000 L1 speakers of all Arabic varieties"

- ^ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/. (Hebrew->Population total all countries, [1])

- ^ Ethnologue report for Maltese, retrieved 2008-10-28

Literatura

[uredi | uredi izvor]- Afsaruddin, Asma; Zahniser, A. H. Mathias (1997). Humanism, Culture, and Language in the Near East: Studies in Honor of Georg Krotkoff. Winona Lake, Ind.: Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-020-0. JSTOR 10.5325/j.ctv1w36pkt. doi:10.5325/j.ctv1w36pkt.

- Austin, Peter K., ur. (2008). One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25560-9.

- Baasten, Martin F. J. (2003). „A Note on the History of 'Semitic'”. Ur.: Baasten, M. F. J.; Van Peursen, W. Th. Hamlet on a Hill: Semitic and Greek Studies Presented to Professor T. Muraoka on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday. Peeters. str. 57—73. ISBN 90-429-1215-4.

- Bennett, Patrick R. (1998). Comparative Semitic Linguistics: A Manual. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 1-57506-021-3.

- Blau, Joshua (2010). Phonology and Morphology of Biblical Hebrew. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-129-0.

- Coghill, Eleanor (2016). The Rise and Fall of Ergativity in Aramaic: Cycles of Alignment Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-872380-6.

- Davies, John (1854). „On the Semitic Languages, and their relations with the Indo-European Class. Pt I. On the Nature and Development of Semitic Roots”. Transactions of the Philological Society (10).

- Davies, John (1854). „On the Semitic Languages, and their relations with the Indo-European Class. Pt II. On the Connection of Semitic Roots with corresponding forms in the Indo-European Class of Languages”. Transactions of the Philological Society (13).

- Dolgopolsky, Aron (1999). From Proto-Semitic to Hebrew. Milan: Centro Studi Camito-Semitici di Milano.

- Eichhorn, Johann Gottfried (1794). Allgemeine Bibliothek der biblischen Literatur [General Library of Biblical Literature] (na jeziku: nemački). 6.

- Brock, Sebastian (1998). „Syriac Culture, 337–425”. Ur.: Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter. The Cambridge Ancient History. 13: The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. str. 708—719. ISBN 0-521-85073-8.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1999). „The Diachronic Typological Approach to Language”. Ur.: Shibatani, Masayoshi; Bynon, Theodora. Approaches to Language Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. str. 145—166. ISBN 0-19-823866-5.

- Bergsträsser, Gotthelf (1995). Introduction to the Semitic Languages: Text Specimens and Grammatical Sketches. Prevod: Daniels, Peter T. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-10-2.

- Garbini, Giovanni (1984). Le lingue semitiche: studi di storia linguistica [Semitic languages: studies of linguistic history] (na jeziku: italijanski). Naples: Istituto Orientale.

- Garbini, Giovanni; Durand, Olivier (1994). Introduzione alle lingue semitiche [Introduction to Semitic languages] (na jeziku: italijanski). Brescia: Paideia.

- Goldenberg, Gideon (2013). Semitic Languages: Features, Structures, Relations, Processes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964491-9.

- Hackett, Jo Ann (2006). „Semitic Languages”. Ur.: Keith Brown; Sarah Ogilvie. Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. str. 929—935. ISBN 9780080877754 — preko Google Books.

- Harrak, Amir (1992). „The ancient name of Edessa”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 51 (3): 209—214. JSTOR 545546. S2CID 162190342. doi:10.1086/373553.

- Hetzron, Robert (1997). The Semitic Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05767-7.

- Hetzron, Robert; Kaye, Alan S.; Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2018). „Semitic Languages”. Ur.: Comrie, Bernard. The World's Major Languages (3rd izd.). London: Routledge. str. 568—576. ISBN 978-1-315-64493-6. doi:10.4324/9781315644936.

- Hudson, Grover; Kogan, Leonid E. (1997). „Amharic and Argobba”. Ur.: Hetzron, Robert. The Semitic Languages. New York: Routledge. str. 457—485. ISBN 0-415-05767-1.

- Izre'el, Shlomo (1987c), Canaano-Akkadian (PDF)

- Kiraz, George Anton (2001). Computational Nonlinear Morphology: With Emphasis on Semitic Languages. Cambridge University Press. str. 25. ISBN 9780521631969. „The term "Semitic" is borrowed from the Bible (Gene. x.21 and xi.10–26). It was first used by the Orientalist A. L. Schlözer in 1781 to designate the languages spoken by the Aramæans, Hebrews, Arabs, and other peoples of the Near East (Moscati et al., 1969, Sect. 1.2). Before Schlözer, these languages and dialects were known as Oriental languages.”

- Kitchen, A.; Ehret, C.; Assefa, S. (2009). „Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East”. Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 276 (1668): 2703—10. PMC 2839953

. PMID 19403539. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0408.

. PMID 19403539. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0408. - Kitto, John (1845). A Cyclopædia of Biblical Literature. London: W. Clowes and Sons. „That important family of languages, of which the Arabic is the most cultivated and most widely-extended branch, has long wanted an appropriate common name. The term Oriental languages, which was exclusively applied to it from the time of Jerome down to the end of the last century, and which is even now not entirely abandoned, must always have been an unscientific one, inasmuch as the countries in which these languages prevailed are only the east in respect to Europe; and when Sanskrit, Chinese, and other idioms of the remoter East were brought within the reach of our research, it became palpably incorrect. Under a sense of this impropriety, Eichhorn was the first, as he says himself (Allg. Bibl. Biblioth. vi. 772), to introduce the name Semitic languages, which was soon generally adopted, and which is the most usual one at the present day. [...] In modern times, however, the very appropriate designation Syro-Arabian languages has been proposed by Dr. Prichard, in his Physical History of Man. This term, [...] has the advantage of forming an exact counterpart to the name by which the only other great family of languages with which we are likely to bring the Syro-Arabian into relations of contrast or accordance, is now universally known—the Indo-Germanic. Like it, by taking up only the two extreme members of a whole sisterhood according to their geographical position when in their native seats, it embraces all the intermediate branches under a common band; and, like it, it constitutes a name which is not only at once intelligible, but one which in itself conveys a notion of that affinity between the sister dialects, which it is one of the objects of comparative philology to demonstrate and to apply.”

- Kogan, Leonid (2012). „Proto-Semitic Phonology and Phonetics”. Ur.: Weninger, Stefan. The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- Kuntz, Marion Leathers (1981). Guillaume Postel: Prophet of the Restitution of All Things His Life and Thought. The Hague: Nijhoff. ISBN 90-247-2523-2.

- Kogan, Leonid (2011). „Proto-Semitic Phonology and Phonetics”. Ur.: Weninger, Stefan. The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- Levine, Donald N. (2000). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society (2. izd.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

- Lipiński, Edward (2001). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar (2nd izd.). Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 90-429-0815-7.

- Mustafa, Arafa Hussein. 1974. Analytical study of phrases and sentences in epic texts of Ugarit. (German title: Untersuchungen zu Satztypen in den epischen Texten von Ugarit). Dissertation. Halle-Wittenberg: Martin-Luther-University.

- Moscati, Sabatino (1969). An Introduction to the Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages: Phonology and Morphology. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Moscati, Sabatino (1958). „On Semitic Case-Endings”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 17 (2): 142—144. S2CID 161828505. doi:10.1086/371454.

- Müller, Hans-Peter (1995). „Ergative Constructions In Early Semitic Languages”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 54 (4): 261—271. JSTOR 545846. S2CID 161626451. doi:10.1086/373769.

- Nebes, Norbert (2005). „Epigraphic South Arabian”. Ur.: Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-05238-2.

- Ullendorff, Edward (1955). The Semitic Languages of Ethiopia: A Comparative Phonology. London: Taylor's (Foreign) Press.

- Owens, Jonathan (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Arabic Linguistics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199344093.

- Phillipson, David (2012). Foundations of an African Civilization, Aksum and the Northern Horn 1000 BC-AD 1300. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781846158735. Pristupljeno 6. 5. 2021. „The former belief that this arrival of South-Semitic-speakers took place in about the second quarter of the first millennium BC can no longer be accepted in view of linguistic indications that these languages were spoken in the northern Horn at a much earlier date.”

- Ruhlen, Merritt (1991). A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1894-6. „The other linguistic group to be recognized in the eighteenth century was the Semitic family. The German scholar Ludwig von Schlozer is often credited with having recognized, and named, the Semitic family in 1781. But the affinity of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic had been recognized for centuries by Jewish, Christian and Islamic scholars, and this knowledge was published in Western Europe as early as 1538 (see Postel 1538). Around 1700 Hiob Ludolf, who had written grammars of Geez and Amharic (both Ethiopic Semitic languages) in the seventeenth century, recognized the extension of the Semitic family into East Africa. Thus when von Schlozer named the family in 1781 he was merely recognizing genetic relationships that had been known for centuries. Three Semitic languages (Aramaic, Arabic, and Hebrew) were long familiar to Europeans both because of their geographic proximity and because the Bible was written in Hebrew and Aramaic.”

- Sánchez, Francisco del Río (2013). Monferrer-Sala, Juan Pedro; Watson, Wilfred G. E., ur. Archaism and Innovation in the Semitic Languages. Selected Papers. Córdoba: Oriens Academic. ISBN 978-84-695-7829-2.

- Smart, J. R. (2013). Tradition and modernity in Arabic language and literature. Smart, J. R., Shaban Memorial Conference (2nd : 1994 : University of Exeter). Richmond, Surrey, U.K.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-13678-812-3.

- Versteegh, Kees (1997). The Arabic Language. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11152-2.

- Waltke, Bruce K.; O'Connor, Michael Patrick (1990). An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax. 3. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-31-5.

- Watson, Janet C. E. (2002). The Phonology and Morphology of Arabic (PDF). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-824137-2. Arhivirano iz originala (PDF) 2016-03-01. g. — preko Wayback Machine.

- Woodard, Roger D., ur. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Syrio-Palestine and Arabia (PDF). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wright, William; Smith, William Robertson (1890). Lectures on the Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [2002 edition: ISBN 1-931956-12-X]

Spoljašnje veze

[uredi | uredi izvor]- Semitic genealogical tree (as well as the Afroasiatic one), presented by Alexander Militarev at his talk "Genealogical classification of Afro-Asiatic languages according to the latest data" (at the conference on the 70th anniversary of Vladislav Illich-Svitych, Moscow, 2004; short annotations of the talks given there

- Pattern-and-root inflectional morphology: the Arabic broken plural

- Ancient snake spell in Egyptian pyramid may be oldest Semitic inscription

- Swadesh vocabulary lists of Semitic languages Архивирано на сајту Wayback Machine (9. јануар 2019) (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)